intro to midi generator music

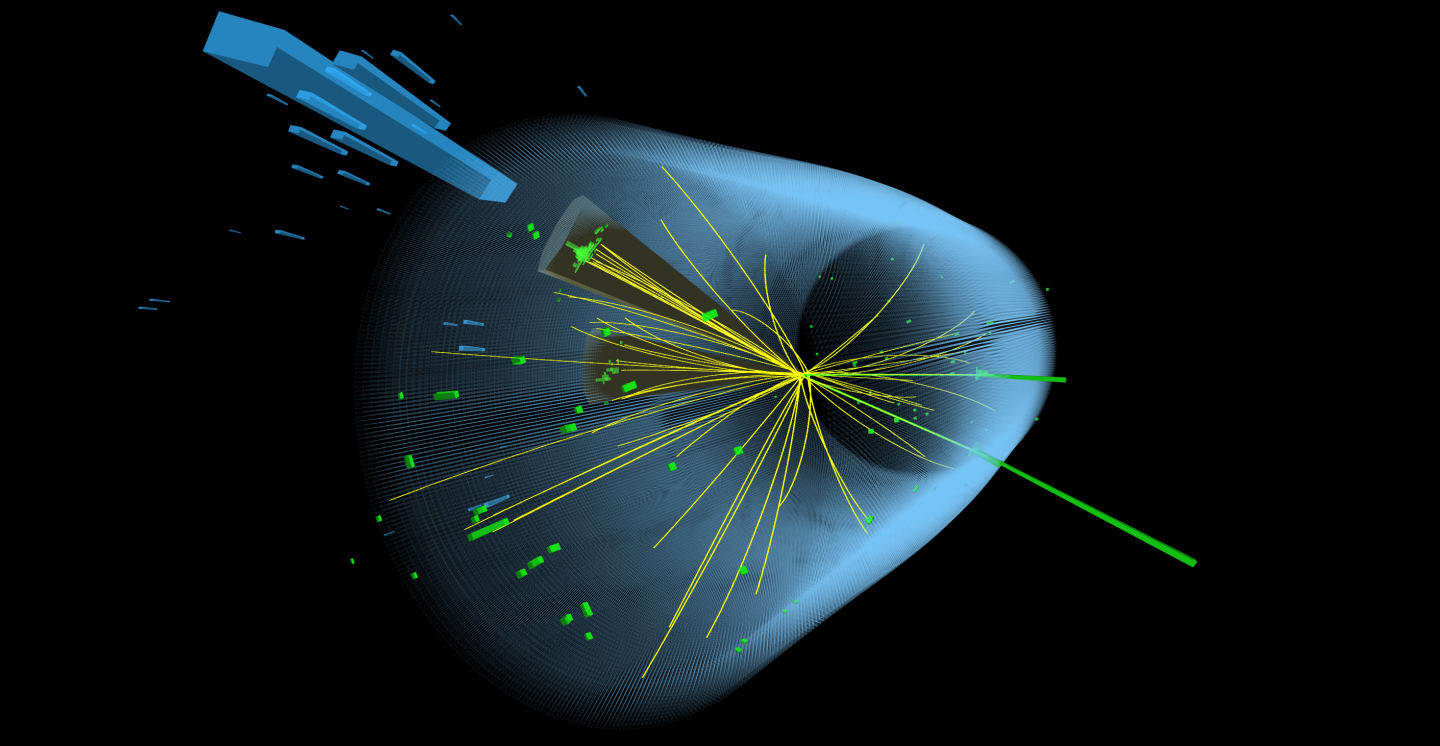

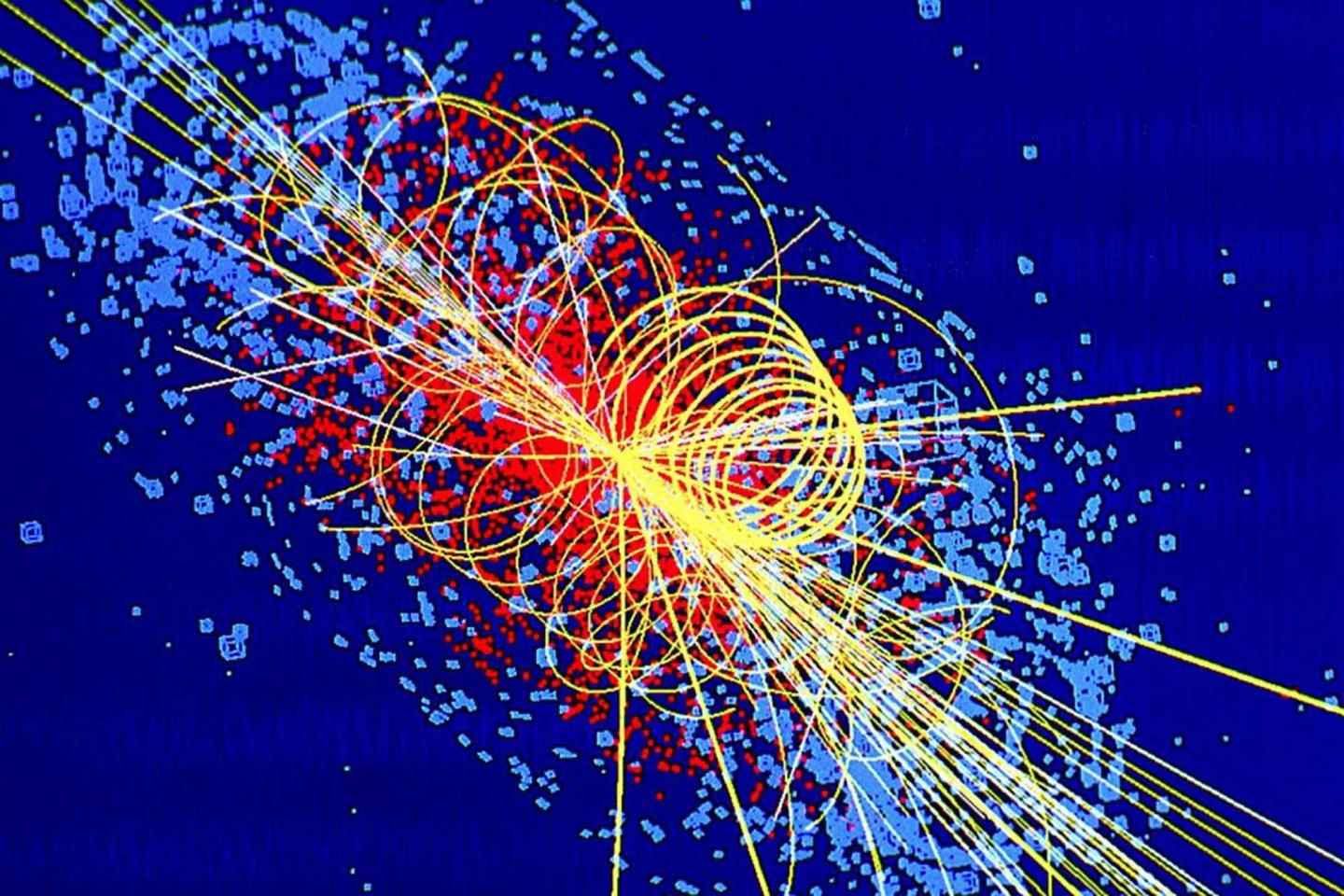

two different diagrams can represent the same particle collision. here are two representations of collisions from cern, relating to the higgs boson detection, although i doubt they both relate to the exact same collision.

two different tracks can be made from the same midi. (here is an example, the same midi played by tenori-on, vs. ableton)

most of what we think of as music -- genre, style, tempo -- is not really a crucial part of the composition. production elements can be changed completely. these versions of styling the same composition hold vastly outsized influence in defining how well a song fits a genre.

the composition itself, the precise pitches and rhythms that, independent of instrumentation, sound, or feel, make up what could be described as its underlying data -- have an undersized influence on genre. some genres specify a handful of characteristic rhythms, chord progressions, or modalities, but these rules can be bent or broken without leaving the wheelhouse of the genre, much more eaisly than production elements can be.

i like to think of my work as though each of the compositions are particle collisions, and each of the finished tracks (or alternate versions) are data visualizations describing this precise configuration.

midi generators provide a theoretically limitless stream of underlying compositions. most that i have tried use something like a shuffle button to randomize the output, jumping around the space of all configurations avaialble to that algorithm without any directed intent. some use silders to navigate to immediately adjacent areas in this configuration-space. i have not seen many that allow you to navigate output in more robust or intentional ways than this.

i think music is an ideal case study for working with machine learning, neural network, or artificial intelligence, specifically because it's such an oversimplified context. a midi track is a two dimensional output, usually with variation over 7 notes in a scale.

to me it is obvious that the next step to overcome diminishing gains in this style of computing would be to develop better navigation tools than a shuffle button.

as a listener, music produced this way may be somewhat alienating, since it's trivially easy for me to produce way more music than anyone would want to listen to (and i haven't even attempted to automate production choices, which would vastly increase the speed at which i could produce mediocre garbage). but perhaps if you understand them as "some of the interesting configurations i found wandering around a very large potentially-generatable dataset at random," perhaps it will be easier to understand why i polished which rocks i did. i only took one path, i didn't see all the rocks. the finished result depends a lot on my skill as a DIY producer -- which is not really where i consider my focus to be.

each midi generator i've worked with is unique, they generate output that is identifiably distinct. this relates to input -- a machine learning algorithm that is trained on a dataset of video game music will sound different than the same one trained on a classical dataset, and each of these may generate output that is distinct from using different training methods on the same datasets. what is included in the training data also influences the output -- a classical dataset that excludes beethoven may generate output that is potentially distinguishable from one that includes him. although it make take a trained ear to recognize that specific example, it's easy to imagine how the principle generalizes.

there is a theoretical total configuration space for midi. in theory, you have to reckon with whether to include the infinite timescale or not, but in practice, most people (other than john cage) don't write compositions longer than say, 4 or 12 minutes, maybe depending on genre. (of course symphonies or concept albums can be much longer, but these are usually split into smaller individual compositions. most midi generators only reckon with the smaller versions, i don't know of any that have tried to train for, say, narrative structure over the course of the opera canon. theoretically you could, but how much of it is identifiable from pitch and rhythm alone? in practice, pitch is also continuous and not discrete, but as far as i know, microtonal music has never been on trend.) so, you could say, excluding infinities, music is theoretically solvable.

the contributions that the underlying data makes to genre are collective. within a genre or style, certain choices become probabilistically more likely. a genre is a limited area from the total configuration space.

most of the music we listen to is confined to an extremely limited area out of the possible configuration space. you know, like a dataset of particle collisions, all originating from the same identical experimental setup at the same collider using the same material. this is not particularly profound, i just think it's funny.

you could rank these tools on a scale of how much of the configuration space they are able to access as output. a synth from the 80s that has an arpeggiator can access a surprisingly large amount of it (although it is in some sense programmatically hardcoded, where neural networks are more probabilistic. tools that do not make their own "choices" in this rather silly sense would have access to a smaller area of the total space). the area that i could have accessed without using any of these tools is vanishingly small.

i apologize for writing a rather meandering essay, but these are some of the foundational principles that i don't really see talked about much, in discussions and review of the past couple decades of algorithm-driven computing. i think these things are perhaps more obvious is a subjective, simplified context. these principles are less obvious in more traditional, bigger-data applications.